…and why do some folk say it doesn’t work?

The first full topic I want us to dig into seems pretty darn straightforward. But, like so many things related to how we raise and care for our companion dogs, it can start to get a bit confusing if you’re a pet parent looking into it on your own.

Let’s talk about positive reinforcement.

Buckle in. This is a longer post, but it’s such an important one for us to explore. And, I promise, there will be some cute pics along the way!

*************

Look anywhere online for information about dog training and you’re likely to come across the phrase “positive reinforcement.” (It even appears on my website!)

What does that really mean? If a trainer says they are a “positive reinforcement” trainer, what does it actually tell you?

I mean, it certainly sounds pretty good and, well, positive…

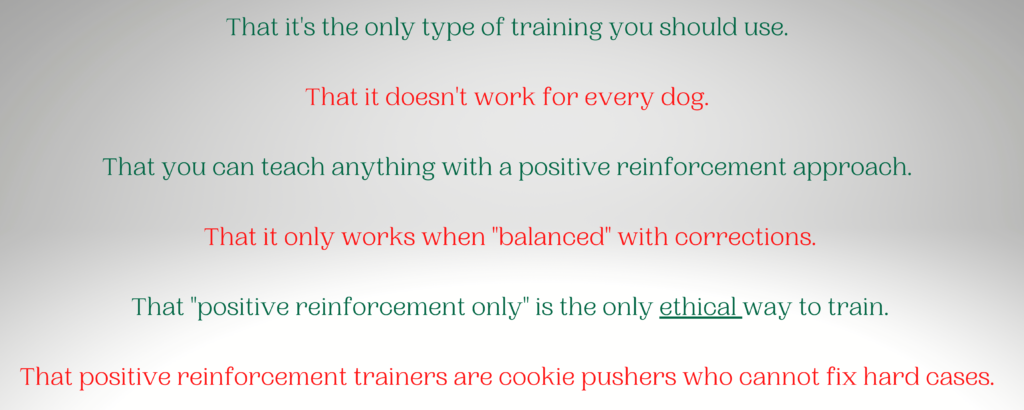

Then again, if you look around the internet (and especially on “dog expert” accounts on platforms like Youtube, Instagram, Tik Tok, and Facebook) you’re likely to fall into a weird pit of mixed messaging about positive reinforcement and those who use it. You’ll probably come across sentiments like this:

Yikes! That’s confusing. What on earth is going on here?

While explaining positive reinforcement training itself is pretty straight forward, the cultural messaging around it is not. We’re going to dig into that at the end, because it’s critical you as a pet guardian understand all the mixed messaging you get about how to train your dog. Before we peer into that rabbit hole, though, let’s get our footing by defining what positive reinforcement actually is, what it means when we say we’re using it in training. Everybody, it’s time to peak into behavioral science!

*************

The fact that we—humans and animals—learn from our environment seems a pretty comfortable, no-arguments-needed truth. Just consider your experience of the world in terms of actions and consequences and you’ll start to see a pattern. When we do something and it results in something we like and want more of (whether we’re consciously aware of it or not), we tend to do it more. For example:

I like feeling full, so I eat food regularly enough to feel full more often.

I like the taste of specific flavors, so I seek out and eat foods with those flavors.

In these examples, the consequence I like and want more of is called Reinforcement. It reinforces the behavior that happened immediately before it.

On the flip side, if we do something and it produces results that we do not like, we tend to stop doing that action or at least do it less often:

I eat from a certain restaurant and soon after get food poisoning, so I develop an aversion to that food and stop going to that restaurant.

When a consequence makes a behavior happen less often, it is called Punishment.

So, Reinforcement is a consequence that makes a behavior more likely to happen again in the future, and Punishment is a consequence that makes a behavior less likely to happen again in the future.

Nothing particularly ground breaking in this, is there? We all experience Reinforcement and Punishment every single day. They are the engines that drive learning, and learning keeps us alive.

Here’s another thing about Reinforcement and Punishment that make them efficient engines for learning: the closer to the behavior the consequence occurs, the more likely it is you will associate the two things and change your behavior in the future. Take this example:

I eat too many sugary foods (behavior) and observe that I start gaining weight (consequence).

In the above, the punishing consequence (weight gain) occurs a long while after the behavior (eating all the tasty sugary foods). If I understand the two things are connected, I might consciously try to change my behavior: maybe my doctor tells me if I want to lose weight I have to stop with the daily donuts, so I do. But, what if that is never explained to me? Am I likely to just instinctively understand the daily donut causes the weight gain? Unlikely. But if I ate a donut and immediately gained 10 pounds? Oh, boy!

Behavior is most impacted by immediate consequences, when the association between the behavior and consequence is easy to make.

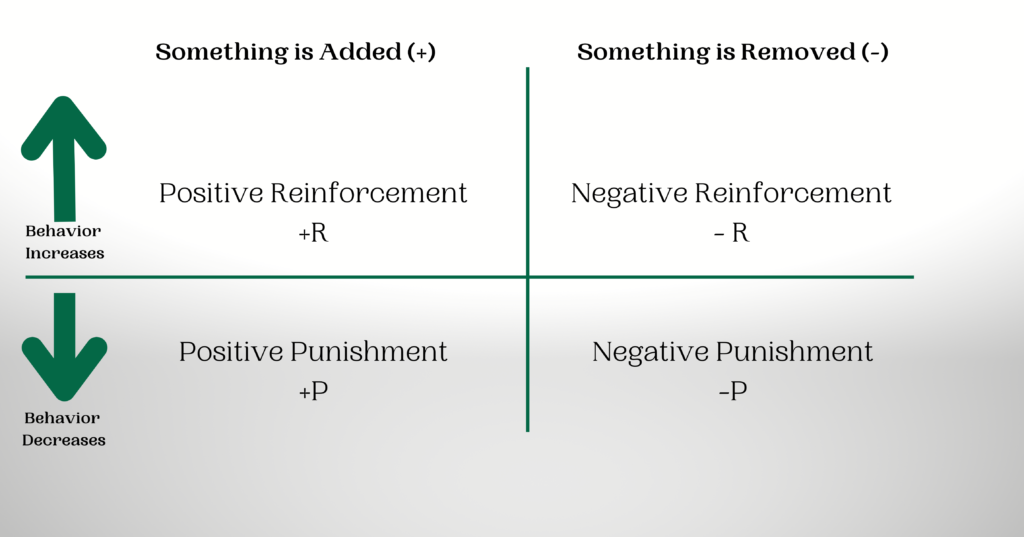

So, that’s Reinforcement explained. Where does the Positive come in?

In the case of “positive reinforcement,” Positive does not mean good or enjoyable. It simply means “added.” Think of it like a plus sign: in Positive Reinforcement, reinforcement is added (+) as the outcome.

And who, exactly, is adding it? It depends. Reinforcement might be “added”

- by the environment (I push a door and it opens; if I wanted it to open, the behavior of pushing is reinforced)

- by internal mechanisms (I eat the food and feel full, the behavior of eating is reinforced)

- by someone outside myself wanting to influence my behavior (my husband says “thank you” as I wash dishes, and my behavior of dish washing is reinforced).

Similarly, the consequence of punishment can be added (+), which is called Positive Punishment. Consequences can also be taken away or subtracted (-), which is called Negative Punishment or Negative Reinforcement. All in all, these four possible outcomes (Reinforcement added, Reinforcement removed, Punishment added, and Punishment removed) are referred to as the Quadrants of Operant Conditioning.

When trainers are working with an animal, we’re usually using at least one of these quadrants intentionally. (More than one of these can be in play—intentionally or not—but that’s a post for another day). With Positive Reinforcement-focused training, the trainer is purposefully adding something the learner wants immediately after a behavior happens to make it happen more. Such as:

I ask my dog to sit. His butt touches the ground. I immediately provide a treat.

Assuming my dog likes treats and will do things with his body to make them appear, I can safely wager his butt is more likely to touch the ground after I say “sit” in the future. I have applied Positive Reinforcement.

And that, in a nutshell, is Positive Reinforcement and how it works!

Whew!!! You just worked through a BIG chunk of info. Shall I reinforce you with a cute picture of puppies and kittens? Yeah, I think so:

©by Liliya Kulianionak via Canva

*************

Now for the nitty gritty stuff: why do you need to know all this and why does it even cause debate?

First, here’s why I want you, a dog guardian, to know it.

Understanding the very basics of how we all learn sets us up for understanding these two incredibly important facts that help us shape the experiences and actions of others:

- All of us are always, always learning. We are doing it 100% of the time we are awake. You take an action, a consequence happens and what you do in the future is shaped by it. Previous experience of Punishment and Reinforcement are constantly and quietly determining our next moves. This happens whether you intend it to or not, whether you are conscious of it or not. This is true for our animals, your partner, your children, and yourself. We are all shaped by previous experience.

So, if your dog noses along the counter, finds a tasty stick of butter and eats it? Reinforcement occurred. They are more likely to nose along the counter to find tasty things in the future.

If your dog begins lunging and barking at another dog that startles them on a walk and, miraculously, that dog is walked the other direction? Reinforcement occurred. They are more likely to bark and lung at startling dogs in the future.

Behaviors continue or disappear because of the consequences that follow them. Period.

This means that if you want to intentionally change a particular behavior, you need to be aware of what reinforcement might be maintaining it. If the behavior is one you like, you want to ensure it is reinforced more. If it’s one you don’t like, you need to strive not to reinforce it or prevent it from being reinforced by the environment.

Okay, seems pretty simple, right? We should just be diligent about reinforcing what we like and punishing what we don’t like…right?

Well, not exactly. First because we do not always have great control over what our dogs find reinforcing or punishing. But additionally…

- Not only are we always learning via consequences, we are also constantly forming emotional associations with those consequences. Generally, those emotional associations fall into one of two categories: “good” emotions, like happiness, excitement, pleasant anticipation, even joy…and “bad” emotions, like fear, sadness, frustration, and anger.

You cannot remove emotions from the learning equation. Emotions play an important role. If I am fearful of a consequence, I am more likely to avoid it in the future. If I love a consequence, I’ll work harder to earn it in the future.

Emotions influence our behavior but they also impact our quality of life. We instinctively know that frequently experiencing the “bad” emotions can negatively impact welfare.

And we have learned that certain types of consequences fuel certain emotions:

- Positive reinforcement scenarios are more likely to build emotions of happiness, confidence, and joy.

- Positive punishment scenarios are more likely to build emotions of frustration, distress, fear, anxiety, and anger.

Now, we cannot directly control what emotions are experienced by those we are teaching or training, but we still need to be very aware that the consequence we select when teaching WILL bring emotional experiences along for the ride.

I could dig pretty deep into why intentionally using techniques that cause fear, anxiety, and distress is not a good idea or a fair choice to impose on another. Fortunately, the absolutely amazing PhD behaviorist Susan Friedman already did so, in her awesome article Effectiveness Is Not Enough. I always recommend aspiring dog and behavior nerds take a look at this and think about how we train our dogs, our children, even ourselves.

Dr. Friedman’s awesome article boils all the above down to a critical take away: we understand how crucial the “Do No Harm” approach is in modern medicine for ethical application of care. It guides what options and treatments we pursue or even offer. So…why should we think any differently about it when it comes to changing the way another (animal or human) thinks and learns?

We still need to always approach it from a firm “Do No Harm” footing.

Adding unnecessary fear or anxiety into an animal’s life is most definitely doing harm.

This is why trainers following modern best practices (recommended by big thinking groups like the International Association of Animal Behavior Consultants and the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior) will avoid using training techniques rooted in positive punishment. No matter how those punishment-centric techniques are prettied up with terminology about leadership, “corrections” or “reminders” about good behavior, they rely on fear, pain or avoidance.

There is an entire Humane Hierarchy of interventions that modern trainers consider as we work with a pet, to ensure we are embracing a “Do No Harm” approach. Positive Reinforcement is high on the hierarchy. Punishment (both positive and negative) are at the bottom and caution should be used before considering them.

All this does not mean a good trainer will never, ever intentionally use punishment in training (but if they do, they’ll have literally tried everything else first and be confident the behavior change outcome is worth the risk of emotional harm). It also does not mean you cannot accidentally create frustration in a dog while using positive reinforcement.

It DOES mean you are much, much less likely to cause harm when attempting to change the behavior of another from a Positive Reinforcement-centric approach.

And yet…

*************

All across our country, many, many dog trainers still recommend intentionally using positive punishment to change our dogs’ behavior. They may do it using painful tools like shock or prong collars, or with pokes, prods, knees to the chest, smacks, rolling dogs and providing collar “pops” with slip leads or choke chains. Yes, they may also use Positive Reinforcement, but only in combination with punishment. The term we see used most often for this is “balanced” training. Supporters of these approaches believe you cannot reliably train without punishment. They even argue that just training with positive reinforcement is ineffective. It won’t work for every or even most dogs, and instead discipline and corrective training produce better, faster results and even save dogs’ lives.

Yet, several studies have actually shown that not only is positive reinforcement on its own as effective in training as punishment, it can be more effective! (Go ahead, indulge the inner dog nerd and check out some actual study abstracts here and here and here).

It’s not that trainers who use or recommend these techniques want to hurt or scare dogs. Usually, quite the opposite. These techniques are recommended specifically to help dogs, theoretically to improve their lives by helping them behave in ways humans can tolerate.

So, when all of us just want happier and safer dogs, and when ongoing research keeps pointing us in the directions toward positive reinforcement and away from punishment…why are we still intentionally using so much punishment with our dogs? And why are we still arguing about whether we should?

Why do we still see just as many posts and videos encouraging you to punish your dog as those recommending positive reinforcement?

Well…this has way more to do with humans, our culture and the stories we tell ourselves than it has to do with dogs.

We, as a society, are pretty obsessed with punishment.

We punish a lot. We reinforce a little. We are constantly fed a narrative from many, many directions that “discipline” is good, and that those who “break the rules” (even rules that are unfair, or not understood, or even unstated) should pay for it.

Dog training is a microcosm of the bigger picture: we are told to punish the heck out of others to get our way, and a lot of times, we’re told doing so is for their own good. In spite of lots and lots of research telling us the exact opposite. This understanding has been so deeply entrenched in our knowledge of relationships–including those with our dogs!–that moving away from it both feels scary and gets labeled as “soft” or “coddling” or “ineffective.”

Yet, positive reinforcement is often a better strategy for changing behavior long term. Mindfully reinforcing behaviors we like not only strengthens the nice behaviors, it often prevents the development of behaviors we don’t like, or at least reduces them by replacing them with the nicer alternatives.

We have some powerful, society-wide baggage to address when it comes to relying so heavily on punishment. I know, I know. I just dropped a big ol’ philosophical bomb into the middle of what maybe should have seemed like a straight forward dog training topic. But this is actually the biggest reason I am passionate that all of us better understanding the actual science of learning. We are saturated with information telling us that punishing others is the only way to change behavior we don’t like. And yet…

When we start to understand why behavior happens, we can actually start to see how it is as easy to reinforce as it is to punish. And, when we suddenly discover we can influence the behavior of those around us in a kind, “do no harm” sort of way, it starts to change how we see the world. Not just your dog, not just your relationship with them. The whole world!

That’s why it’s worth knowing more about what Positive Reinforcement actually is!

(Head’s up: this is actually Part 1 in a three part introductory series thinking about using positive reinforcement instead of punishment-based techniques. Check back later in the month for Part 2).

Click! You made it through a BIG article! Have another puppy picture!

©by Annette Shaff via Canva